News | July 14, 2025

The former NBPA Executive Director, based in Washington, DC, will lead Secretariat’s growing Global Sports Consulting capabilities.

March 13, 2024

Authored by Shalabh Gupta & Amran Nawaz

Article originally published by LawInSport: Breaking the bank or building the game? The tightrope walk of Premier League football finance

Recent months have been eventful for those interested in English football and accounting, with unprecedented developments and excitement off the field. Everton FC received a six-point deduction in the English Premier League (PL)[1] for the alleged breaches of Profit and Sustainability Rules (PSR).[2] Everton FC and Nottingham Forest FC have been charged for breaches during the 2022/23 seasons,[3] and Manchester City FC have also been charged with 115 alleged breaches of PSR.[4] There is also an investigation into Chelsea FC’s funding under its previous ownership.[5]

All of these off-the-pitch events share a common theme: breaches, or alleged breaches, of the PSR. Despite financial regulations not being new to the PL, the spike in financial breaches is unsurprising given the ever-increasing costs for clubs to compete. Potential reasons for the increase in financial breaches include the increases in league-wide investments in squads and footballing infrastructure,[6] unchanged limits of the maximum permitted losses for over a decade,[7] and the looming government mandate for an independent regulator.[8]

This article discusses the application of the current financial regulations (including PSR) to PL clubs and recent trends in compliance with these regulations, and examines certain aspects of the current regulations that the regulators could look to improve upon to deal with issues that arise from creative accounting practices and misaligned incentives.

We previously examined the correlation between a football club’s financial and sporting success.[9] Football clubs make substantial investments in player wages and recruitment to be competitive. This is evident when considering that PL revenues have grown 27 times over the last 20 years, while player wages have grown approximately 36 times during that period.[10]

A PL club must comply with the PSR,[11] which limits the maximum losses over a three-year rolling period[12] to £105 million. Depending on their finishing position, a PL club might also be required to comply with a second set of financial regulations:

A comparison of the abovementioned three sets of rules is provided as follows.

| Description | PL[13] | EFL[14] | UEFA[15] |

| Maximum three-year loss | £15 million | £15 million | €5 million |

| Maximum owner funding over three years | £90 million | £24 million | €55 million |

| Maximum three-year loss (including owner funding) | £105 million | £39 million | €60 million |

| Permitted expenses (i.e., excluded from loss calculation, see footnote 17 for an indicative list of such expenses)[16] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Transactions required to represent “fair market value” | Yes | Yes | Yes[17] |

| Additional financial regulations | No | No | Yes[18] |

In summary, the three regulators are generally consistent in their assessment framework but differ on the maximum losses a club can incur. Regulators are focused on preventing clubs from spending unsustainably, with the objective of promoting financial prudence and improving footballing infrastructure and the quality of on-field performances. However, the influx of significant investment from institutional investors such as private equity and sovereign funds has led to the introduction of sophisticated accounting and financial practices that could prevent the regulators from achieving their goals. In the following sections, we discuss three key issues that regulators could consider in their review of the current framework to assess the financial performance of PL clubs.

It is critical to understand that cash flows and profits are different. While profits indicate the income remaining after all expenses, cash flows indicate the net flow of cash into and out of a business. Further, the intrinsic value of a business is derived from the cash flows it can expect to generate. From an investor’s perspective, a profitable company with positive cash flows is a good, long-term investment based on its ability to remain solvent in times of economic crisis (e.g., relegation in the case of PL clubs, COVID-19, etc.).

The PSR uses the metric “adjusted earnings before tax”[19] to assess a club’s financial performance over a three-year period. In our opinion, a club’s earnings do not present a holistic view of its financial position or performance because an entity may have negative cash flows during a period but still report a profit. Cash flows are generally considered a more robust metric to assess an entity’s financial performance as compared to profits, which can be affected by accounting policies or “creative” practices.

“Revenue is vanity, profit is sanity, but cash is king.”

– Alan Miltz

While these practices do not necessarily affect the financial health of a club, the recent, what some may call, “creative” accounting practices across PL clubs highlight the limitations of relying solely on accounting earnings for PSR compliance.

The most popular example of recent times is Chelsea FC (under its new ownership) signing players under lengthy contracts (reportedly up to eight years) to reduce their reported annual expenses by spreading the amortization of the players’ transfer fee over a longer period.[20] Since then, both UEFA[21] and PL[22] have amended the financial regulations restricting the amortization of transfer fees to a maximum of five years, even if players sign a contract for longer. As these amendments are implemented prospectively, Chelsea FC’s treatment of eight-year player contracts is unaffected by the amendments; demonstrating how accounting practices have been used to comply with PSR without truly reflecting their financial reality.

Further, the cash actually paid by a club for transfer fees is generally unrelated to the amortization of a player contract, which is purely an accounting calculation. Given the rising transfer fees, the clubs generally defer the transfer fee payments over several seasons and include a performance-based contingent component. If the cash paid is greater than the amortization of a player contract in a given year (and continues to be so for consecutive years), situations could arise wherein the club does not have adequate cash to meet its transfer fee liabilities. Therefore, a club’s PSR compliance based on amortization (i.e., a non-cash expense) instead of its outstanding transfer fee liabilities or transfer fee payments may not accurately measure its actual liabilities or cash flows when assessing a club’s financial health.

Similarly, net worth (which is calculated as assets minus liabilities) is a critical metric that banks and other financial institutions use to assess an entity’s financial health, specifically, a potential borrower’s creditworthiness.

In summary, additional financial metrics of a club, such as cash flows and net worth, along with its profits, should be considered, strengthening the PL’s financial regulatory framework and increasing transparency. Adherence to such metrics would improve the financial health of clubs in the long run.

Historically, football clubs have employed different strategies to develop, purchase, and sell players. Several clubs, including Southampton FC and AFC Ajax, have been known to develop and sell younger academy players to larger clubs.[23] Meanwhile, clubs, including Brighton & Hove Albion FC and Borussia Dortmund, have been known to acquire young, talented players for comparatively lower sums, develop them, and subsequently sell them at high values.[24] One may argue that these strategies were not adopted to meet PSR, instead serving as a sustainable revenue source for clubs to reinvest in their squads and infrastructure, thereby ensuring a cycle of development and competitiveness.

Transfers structured as loans with an obligation or an option to buy have also become prevalent. Such transfer structures defer the purchase timing, payment of transfer fees and amortization of the player contracts. A recent example is the loan arrangement for goalkeeper David Raya from Brentford FC to Arsenal FC during the summer 2023 transfer window. Arsenal FC paid a £3 million loan fee for the one-year loan and has the option to purchase the player for £27 million upon completion of the loan.[25] This strategy generally takes advantage of deferring costs and cash flows, and in most cases, it does not adversely affect the financial health of the clubs.

While several factors[26] impact a club’s decision to sell a player, another striking recent trend has been a club’s desire to sell academy players, who are playing in or can break into the first team, to earn “pure profits”. Under the current PSR framework, the profit on the sale of a player is calculated as the difference between the transfer fee and the player’s net book value (i.e., amortized contract amount). Below is a rudimental example illustrating the impact on earnings upon the sale of a purchased player and an academy player.

| Purchased | Academy | ||

| Net book value | [A] | £30 million | £nil |

| Selling price/cash inflow | [B] | £45 million | £45 million |

| Adjusted earnings before tax | [C] = [B] – [A] | £15 million | £45 million |

In the above illustration, while the cash inflow for both transfers is the same (i.e., £45 million), the profits from the two players are vastly different (i.e., £45 million versus £15 million). Therefore, if a club is in a position where it needs to sell players in order to comply with financial regulations, it may be incentivized to sell an academy player (with nil book value) over another player in order to report higher earnings. For example, it has been widely reported that Chelsea FC has been exploring the sale of Connor Gallagher to comply with PSR after spending lavishly on transfers under their new owners. [27]

In summary, selling academy players in order to spend more money potentially undermines the objective of financial stability and player development.[28] In addition, it could eventually reduce the ability of a club to develop and retain players throughout their entire career, as financial imperatives overshadow sporting objectives. Assessing cash flows generated from player sales in addition to profits could help discourage clubs from using short-term fixes that could be detrimental to their long-term financial health.

Recent announcements relating to alleged breaches of PSR by Everton FC (who were in breach due to non-sporting costs and factors)[29] and Nottingham Forest FC (who were in breach of the PSR as of June 2023, but mitigated the situation through player sales by September 2023)[30] have sparked a debate over the appropriateness of fines and penalties being imposed under the PSR.[31]

The stringent application of PSR by the PL (under the looming threat of an independent regulator) coupled with the uncertainty relating to fines and/or penalties for potential breaches precluded many PL clubs from investing in strengthening their squads during the January 2024 transfer window. A total of £112 million was spent by all PL clubs during January 2024 compared to £815 million in January 2023, representing the lowest total spend in over ten years (except for 2021, which was impacted by COVID-19).[32]

The current PSR is centered solely on a maximum loss threshold over three years but does not distinguish between expenditures on sporting activities and non-sporting activities. In contrast, UEFA’s FSR considers three financial assessments for a comparatively holistic assessment of a club’s financial health:

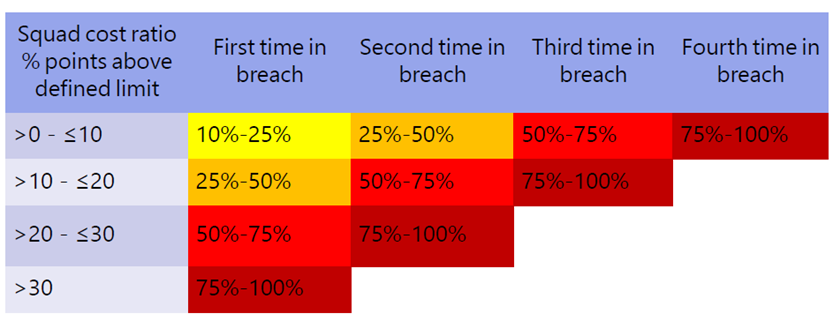

In addition, UEFA provides a “financial disciplinary measure grid” for breaches of the squad cost ratio (as provided below). This penalty system accounts for the severity of the breach, including the amount by which a club exceeds the permitted cost limits and its history of similar breaches.[33] Such a structured penalty grid offers transparency and predictability, enabling clubs to understand the potential consequences of their financial decisions.

In summary, the PL’s PSR regulations should clarify limits relating to sporting costs (e.g., squad) and non-sporting costs (e.g., stadium development and logistics) and outline the fines/penalties relating to specific breaches. This would bring predictability and fairness in penalties and encourage clubs to adopt more sustainable financial practices.

The influx of money and financial sophistication necessitates a robust and dynamic regulatory framework to maintain the competitive nature of the sport and the financial sustainability of clubs.

To summarize, we have discussed the recent trends and issues that are affecting the enforcement of PSR, causing confusion and uncertainty amongst PL clubs, leading to disputes, and precluding the regulators from achieving their goal of improving the financial health of football clubs, including:

These points will help make enforcement of PSR a transparent and predictable process, preserving the thrill of the season’s climax on the deadline day. Or else, the suspense of final match day relegation battles may fade into the anticlimax like a VAR-delayed goal celebration…

Shalabh has provided financial analyses, economic advisory, forensic accounting, quantification of damages and other litigation support services to clients and their counsel for 10 years. He is a Chartered Accountant (CA), a Certified Fraud Examiner (CFE), and a Chartered Business Valuator (CBV).

Amran has more than 8 years of experience in accounting and financial consulting, with specializations in the quantification of damages and valuations in the context of commercial and investment disputes. He is a Chartered Professional Accountant (CPA, CA) and a Chartered Business Valuator (CBV).

[1] Premier League statement, February 2024.

[2] Premier League Handbook, Season 2023/2024, Section E.

[3] Premier League statement, January 2024.

[4] Premier League statement, February 2024.

[5] The Athletic article, “Premier League chief Richard Masters on FFP, club ownership and Saudi Arabia”, August 2023.

[6] Secretariat article, “Valuations of Sports Teams on the Rise: A Tale of Two Continents“, October 2023.

[7] The maximum permitted losses were announced in February 2013, when transfer fees and player wages were significantly less than their current rates.

[8] Mr. Sunak, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, has explained that if the PL is unable to regulate the financial aspect of the competition, then an independent regulator will step in. An independent regulator was a recommendation of the fan-lead review in 2021. As a result, the PL is attempting to demonstrate that it can self-regulate.

[9] Secretariat article, “Valuations of Sports Teams on the Rise: A Tale of Two Continents“, October 2023.

[10] GOV UK, “Still ill? Assessing the financial sustainability of football”, June 2023.

[11] Clubs competing in the PL are subject to PSR set out by the Premier League, whereas clubs competing in other leagues in the English football pyramid are subject to PSR set out by the English Football League.

[12] For instance, in December 2023, the three-year rolling period would be for the seasons 2020/2021, 2021/2022, and 2022/2023.

[13] PSR applicable to clubs competing in the PL. Premier League Handbook, Season 2023/2024.

[14] PSR applicable to clubs competing in the English Football League (i.e., leagues beneath the PL in the football pyramid). The regulations are generally the same as PL clubs, with reduced maximum losses. EFL Handbook, 2023/24.

[15] FSR applicable to clubs competing in UEFA club competitions (i.e., the Champions League or Europa League). UEFA Club Licensing and Financial, Edition 2023.

[16] Permitted expenses across the three regulators include: depreciation and impairment (excluding player registration); women’s football; youth development; community development; COVID-19 costs; finance costs attributable to construction and substantial modification of tangible assets; and leasehold improvements.

[17] UEFA Club Licensing and Financial, Edition 2023, Annexes J.2.1 (m) and J.3.1 (j).

[18] Squad cost requirements and solvency requirements.

[19] Earnings before tax represent the pre-tax income of clubs (i.e., calculated as revenue less expenses). The types of adjustments (i.e., permitted expenses) are provided in footnote 16.

[20] For example, if two players were each signed for £40 million and had contract lengths of four years and eight years, their annual amortization would be £10 million (i.e., £40 million / four years) and £5 million (i.e., £40 million / eight years), respectively. This illustrates that a comparatively longer contract reduces the annual amortization (i.e., increasing the club’s annual earnings).

[21] The Athletic article, “UEFA sets five-year limit on transfer fee amortisation after Chelsea’s January deals for Fernandez and Mudryk”, June 2023.

[22] The Athletic article, “Premier League clubs vote for five-year limit on transfer fee amortisation”, December 2023.

[23] Such as Gareth Bale and Luke Shaw at Southampton FC, and Frenkie de Jong and Matthijs de Ligt at AFC Ajax.

[24] Such as Moisés Caicedo and Alexis Mac Allister at Brighton & Hove Albion FC, and Jadon Sancho and Ousmane Dembélé at Borussia Dortmund.

[25] The Athletic article, “Arsenal complete loan signing of David Raya from Brentford; deal structure, new contract explained”, August 2023.

[26] Such as expiring contracts, off-the-pitch behaviour, deteriorating on-field performances, a player’s desire to play more regularly, etc.

[27] The Athletic article, “Is Conor Gallagher really ‘priceless’ to Chelsea and is he forcing their hand?”, February 2024.

[28] This occurs due to the “pure profits” being generated while the transfer fee of purchased players is amortized over the term of the contract. In the above illustration, the sale of the academy player would generate £45 million of profits in the year of sale. Concurrently, the club could purchase five players for £45 million each on a five-year contract as the amortization for each player would only be £9 million (i.e., £45 million / 5 years) for the year.

[29] The Athletic article, “Everton’s 10-point deduction explained: Why is the sanction so steep, and what happens next?”, November 2023.

[30] The Athletic article, “Everton and Nottingham Forest referred to independent commission over alleged breach of spending rules”, January 2024.

[31] Although the PL prosecutes the clubs, the cases are referred to the chair of the judicial panel, who appoints independent commissions to determine the appropriate sanction.

[32] The Athletic article, “The January transfer window: From £2.36bn to £112m spent – and a collective refusal to gamble”, February 2024.

[33] The grid provides “the level of financial disciplinary measure as a percentage of the licensee’s squad cost ratio excess”. UEFA Club Licensing and Financial, Edition 2023, Annex L.4.

[34] As demonstrated in footnote 19.

The former NBPA Executive Director, based in Washington, DC, will lead Secretariat’s growing Global Sports Consulting capabilities.

Why Funder Forecasts Don’t Belong in Royalty Analysis

In a recent article published by Law360, Managing Director Rick Eichmann explores the economic reasoning behind the U.S. District Court’s decision in Haptic Inc. v. Apple Inc. and why prelitigation funding forecasts should not be conflated with royalty analyses in patent litigation.

SFO’s ‘Cast-Iron Guarantee’ on Self-Reporting Comes With Fine Print

Ben Boorer, writing for Corporate Compliance Insights, examines the UK Serious Fraud Office’s clearest commitment yet to corporate self-reporting, offering a “cast-iron guarantee” of DPA negotiations for companies that self-report and cooperate.