In Antitrust analysis in the United States, the Small but Significant Non-Transitory Increase in Price (“SSNIP”) test is often a key component of market definition analysis, whether performed quantitatively or qualitatively.

In Antitrust analysis in the United States, the Small but Significant Non-Transitory Increase in Price (“SSNIP”) test is often a key component of market definition analysis, whether performed quantitatively or qualitatively. In this analysis, an entity is hypothesized to be a monopolist with respect to a product or set of products that are under consideration to be a relevant market. The analysis asks whether this hypothetical monopolist could profitably impose and sustain a small, but significant non-transitory increase in price (often defined to be a 5% price increase). If the answer is “yes,” the set of products under consideration is a relevant market. If the answer is “no,” the set of products under consideration is expanded successively until the SSNIP can be profitably sustained. The SSNIP test captures economic considerations of substitutability and cross-elasticity of demand by considering potential substitution among competing products and may therefore be used to define both the relevant product and geographic dimensions of the relevant market.

While the SSNIP test has dominated antitrust analyses in the United States, other tests of market definition and market power have seen increasing use in the European Union. One example of an alternative to an SSNIP is the Small but Significant Non-Transitory Decrease in Quality (“SSNDQ”) test. This test is similar to the SSNIP test in that it considers a hypothetical monopolist of a set of products or services but, instead of imposing a hypothetical increase in prices of this product or service, it analyses possible substitution effects following a decrease in the quality of these products or services. Like the SSNIP test, the SSNDQ test can be used to draw the boundaries of a relevant antitrust market and understand the potential for market power.

Notably, in zero-price markets, the European Union has recommended the use of an SSNDQ as an alternative to an SSNIP. While pricing power has historically been a hallmark of market power and may be readily observed in traditional industries, with the rise of the digital economy, many of the world’s largest firms now operate in the zero-price economy. For example, social media companies like Meta, search engines like Google, and digital apps like Yelp are “free” to users, in that users trade their data to the company and its advertisers to use the product or service for $0. Because of this, defining a market using the traditional SSNIP test, or evaluating market power through a pricing analysis, imposes both empirical and even conceptual challenges. Alternatively, using an SSNDQ test allows the fact finder to maintain the zero-price nature of a basket of potentially competitive goods while still considering how consumers may substitute away from certain products given a change in a product’s value – where value contains elements of both pricing and quality.

Indeed, there is some evidence that a greater move towards quality considerations in market definition may be on the horizon. For example, in the DOJ’s recent case against Google related to its monopolization of general search services, Judge Amit Metha, in his opinion, cited evidence of Google’s ability to decrease the quality of its search engine as evidence of its monopoly power in the market for general search services. However, the potential import of an SSNDQ test to the United States would likely bring both additional opportunities and additional considerations for market definition analyses going forward.

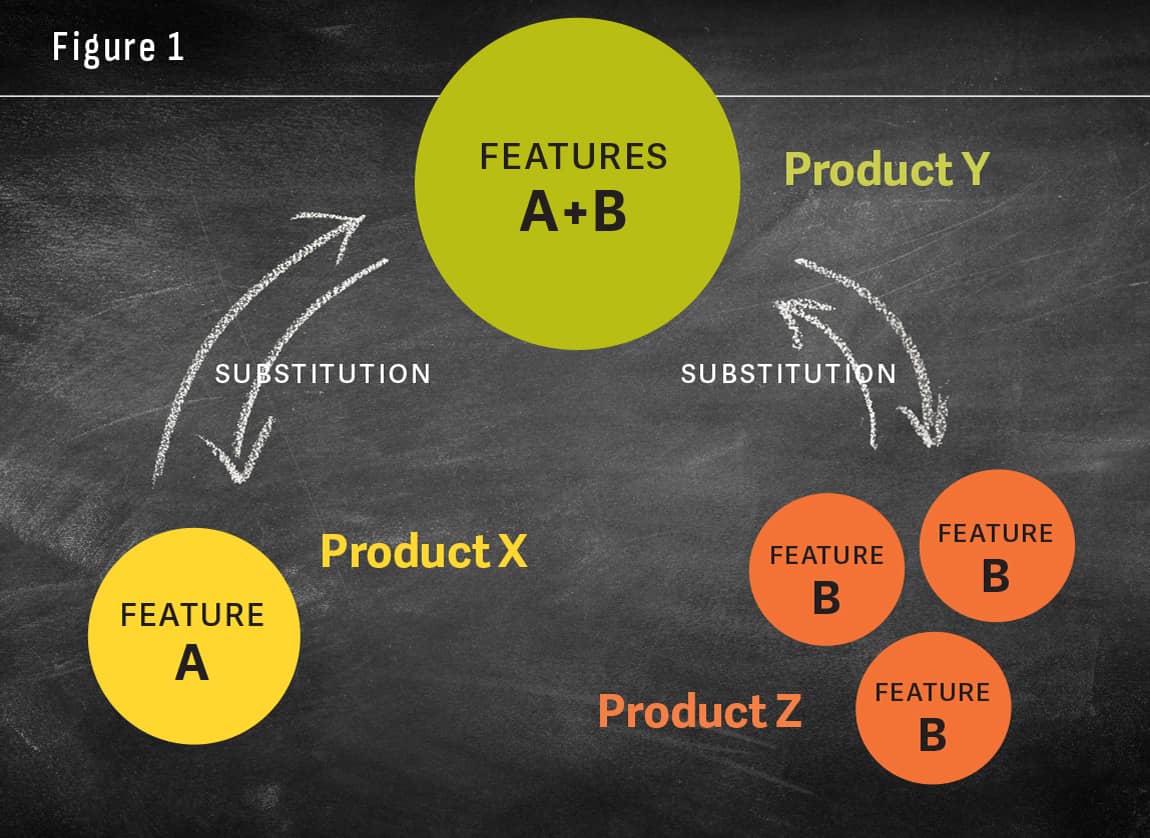

In addition to being useful in zero-price markets, the application of an SSNDQ may also be usefully applied to other complex cases of market definition. For example, an SSNDQ test could generate certain insights when analyzing markets that are characterized by differentiated multi-featured products. Consider the example of a product (“Product X”) that has a single predominant feature and use (i.e., “Feature A”) but competes only with a product (“Product Y”) that contains Feature A but also an additional feature (“Feature B”). Assume there are also several other products (“Products Z”) that contain only Feature B and therefore also compete with Product Y, but not Product X. Assume all products are sold at one price and one cannot purchase the features in Product Y separately. An illustration of this market and consumer substitute patterns is in Figure 1.

Then consider the factfinder tasked with analyzing the dynamics of this market and in particular, analyzing any harm to consumers that could result in Product X being foreclosed from this market. Analyzing this market under a traditional SSNIP test, one may conclude that even if Product X were to be foreclosed from the market, the producer of Product Y would still be unable to raise its prices by an SSNIP if they face significant competition from companies making Products Z. Such an analysis could support the notion that consumers primarily interested in products with Feature A would not be harmed (from a pricing perspective) in the event of the removal of Product X from the market. That is, even if the producer of Product Y was the sole provider of Feature A (through their multi-featured Product Y), there would be no consumer welfare concerns due to the pricing constraints imposed by Products Z.

However, analyzing the same question under an SSNDQ approach, one may reach a different conclusion. If instead of analyzing the power to raise prices by an SSNIP, the factfinder was to consider the producers of Product Y’s ability to decrease in quality of Feature A, a different conclusion emerges. Under this analysis, if Product X were to be foreclosed from the market, consumers primarily interested in products with Feature A could be harmed through this decrease in the quality of Feature A by the producer of Product Y, even if there is no change in Product Y’s price. That is, consumers could be harmed from a quality of value perspective – while they may not pay an increased price for Product Y, they may receive less value from that price if they value Feature A. Under this analysis, it is clear that Products Z, while possibly functioning to constrain price increases for Product Y, cannot sufficiently constrain quality decreases for certain features of Product Y. Such findings could result in a different conclusion regarding the antitrust concerns in the foreclosure of Product X.

Use of the SSNDQ framework in antitrust analysis in the United States may provide additional or alternative insights regarding consumer harm from the perspective of product and/or service quality. This framework may be useful for understanding the market dynamics for zero-price goods. It may also provide insights regarding potential harm to consumers as certain products expand their functionalities. As one concrete example of this, consider the Apple AirPods expansion from standard headsets (which may compete with those from companies like Bose) into hearing aids. Of course, a quality-emphasizing framework will come with certain challenges, a discussion of which is outside the scope of this article.