News | July 14, 2025

The former NBPA Executive Director, based in Washington, DC, will lead Secretariat’s growing Global Sports Consulting capabilities.

Secretariat’s meticulous research and analysis were instrumental in the jury’s damages verdict.

A biopharmaceutical company had exclusively licensed a patent relating to a novel type of cancer immunotherapy that modifies a patient’s T cells to target and kill cancer more effectively. Its primary competitor had previously attempted to license, invalidate, and invent around the patent, but failed. Despite being aware of potential infringement claims against its therapy, the competitor prioritized being first to market for its lead indication, attempting to lock in a sizeable portion of what was viewed to be a blockbuster marketplace. Upon its competitor achieving FDA approval, the company filed patent infringement claims against its primary competitor.

Secretariat was engaged on behalf of the plaintiff to evaluate economic damages in the form of reasonable royalties for the alleged infringement. A legal framework for determination of reasonable royalties specifies an evaluation of a hypothetical negotiation occurring on the eve of infringement between the patent-rights holder and the alleged infringer for rights to the asserted patent. In this case, Secretariat conducted economic analyses of numerous factors the parties to the hypothetical negotiation would have considered, including the economic contribution of the patented technology to the allegedly infringing product, availability of potential non-infringing alternatives, stage of development of licensed technology, competitive relationship between the two parties, financial harms and benefits from use of the patented technology by the alleged infringer, and existing license agreements for comparable technology.

Secretariat submitted an expert report and provided expert testimony at deposition and trial. After an eight-day trial, the jury returned a verdict in favor of Secretariat’s client with a damages award that precisely matched the trial testimony

One method of evaluating reasonable royalties involves an analysis of prior agreements to the asserted technology. Such an approach, called the market approach, involves identifying meaningful economic differences between the circumstances of the prior agreements and those present at the hypothetical negotiation. Differences identified can be accounted for through an adjustment of the financial terms specified in the prior agreements such that the adjusted royalties would appropriately reflect the economic dynamics of the hypothetical negotiation.

For its analysis, Secretariat relied on an agreement to the asserted patent that had granted Secretariat’s client exclusive rights to the patent (the “prior agreement”). Secretariat’s research and analysis identified key differences between the circumstances of the prior agreement and those present at the hypothetical negotiation, including:

Secretariat sought to account for these and other considerations in an economically reasonable and verifiable way.

Secretariat’s analysis of reasonable royalties was informed by extensive economic research and evaluation of case-specific facts. Various aspects of the analysis are discussed below.

Biopharmaceutical licensing: Secretariat’s research documented particular facts about licensing practices that would apply at the hypothetical negotiation: (1) the evidence in the case demonstrated a prevalence of payment structures with combinations of fixed payments and running royalties; (2) the various fixed payments found in evidence often accounted for the resolution of clinical and commercial uncertainty regarding the licensed technology; (3) the evidence was consistent with “late-stage” technology (i.e. those that have undergone significant commercial and clinical development) generally being more costly to license than “early-stage” technologies, with commercial-ready technology generally being the most costly to license; (4) license agreements that would result in the parties maintaining a directly competitive relationship were less common in evidence; rather, agreements appeared to be structured such that would-be competitors work collaboratively; (5) financial terms and royalties in the “collaboration” agreements between commercial entities were generally higher than financial terms from agreements that involve a commercial entity and an academic collaborator as licensor. These observations were supported not only through substantial evidence produced in the case but also Secretariat’s own research on marketplace licensing practices and discussions with industry experts. Based on its research and analysis, Secretariat determined a royalty structure that included both an upfront payment and running royalties would be economically appropriate.

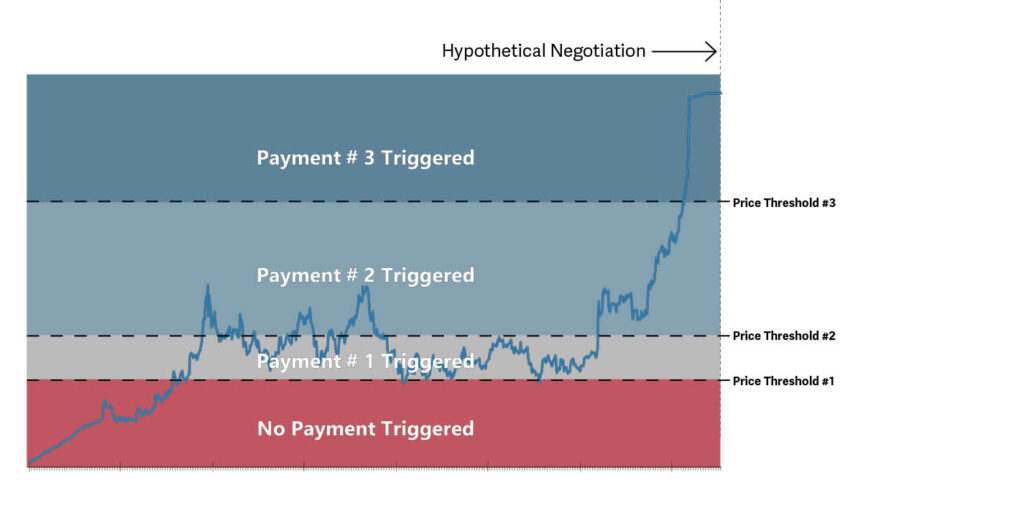

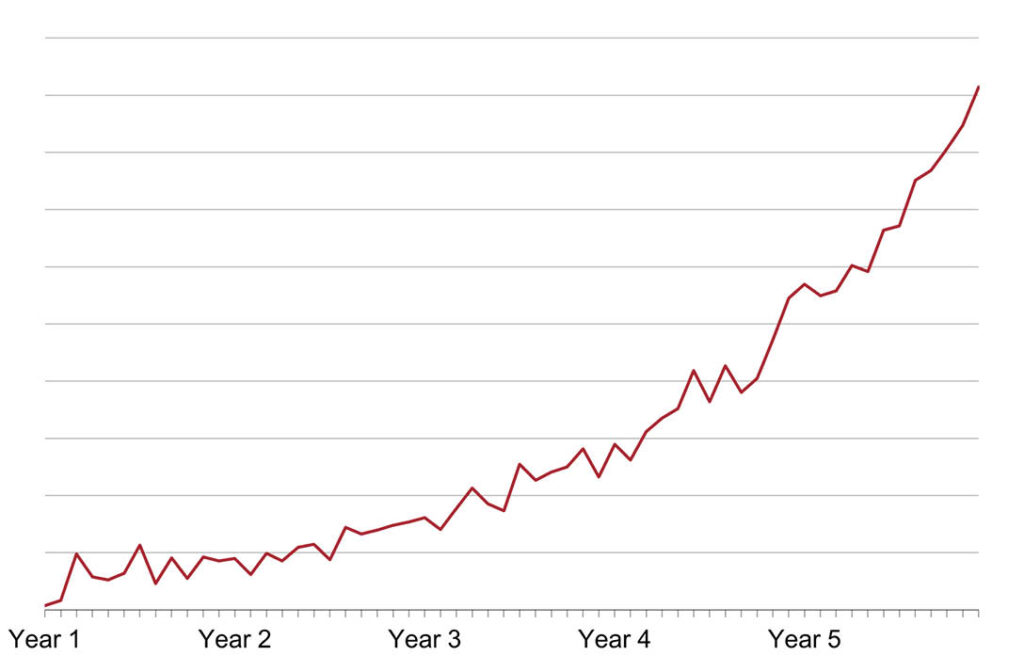

Stage of development: Secretariat demonstrated that certain payments specified in the prior agreement that are tied to stock performance could reasonably account for the advanced stage of development of the patent at issue at the time of the hypothetical negotiation. Secretariat’s analysis demonstrated that stock price and company value were largely based on market expectations about the accused products, and that stock price reflected the increased value of the asserted technology at the time of the hypothetical negotiation. Secretariat applied the terms of the prior agreement to the economic circumstances of the hypothetical negotiation to quantify an adjusted upfront payment accounted for these payments based on stock price, and thus, the advanced stage of development of the patent at issue. See Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows stock price (blue line) over time relative to certain payment-triggering price thresholds as specified in the prior agreement.

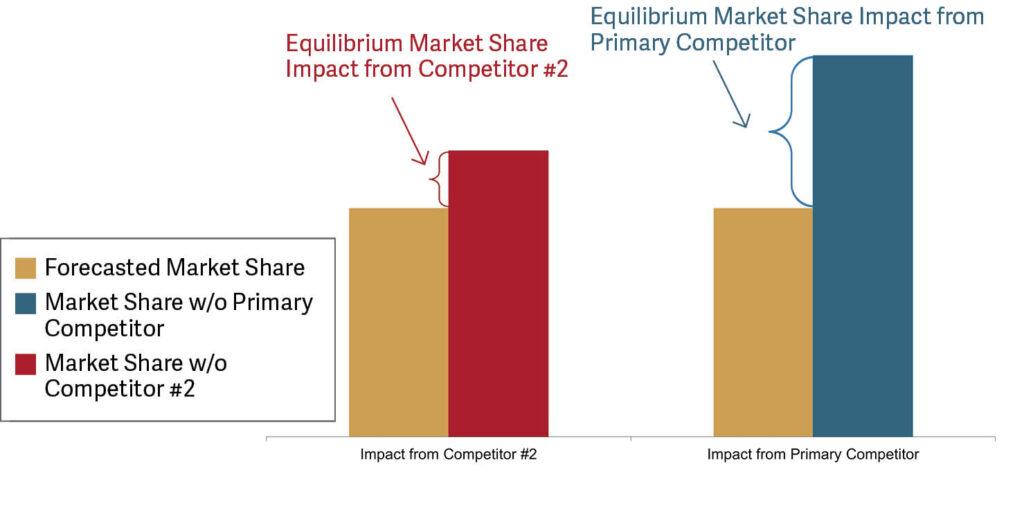

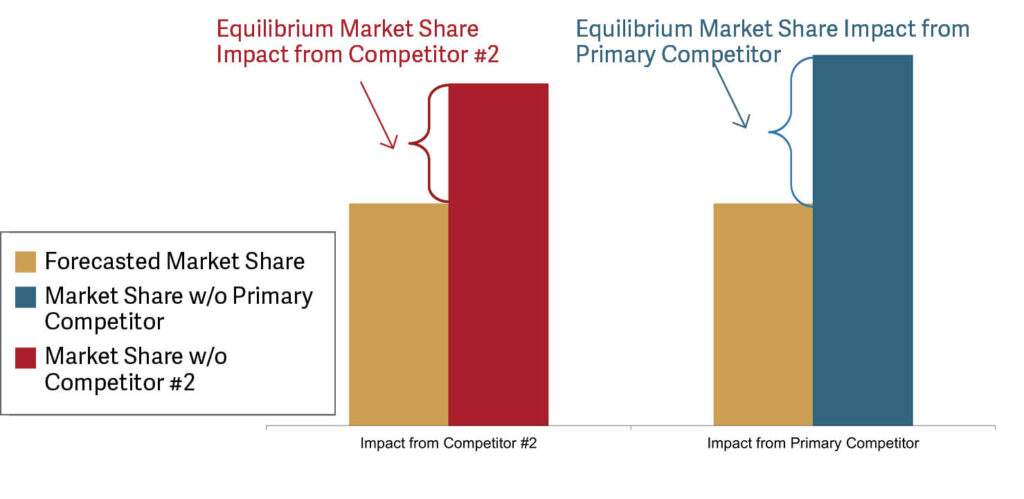

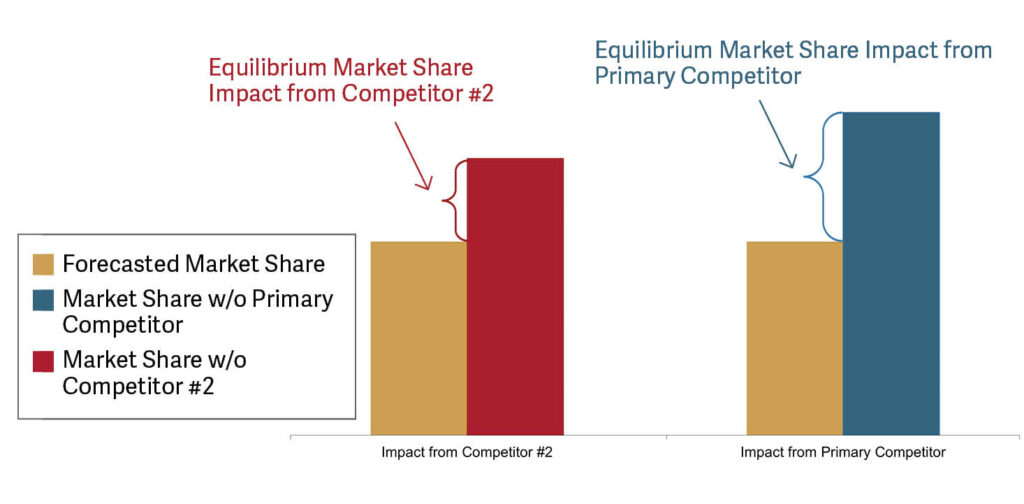

Commercial Relationship: Secretariat’s research revealed three primary participants expected to compete in the marketplace: the plaintiff, the primary competitor/the defendant, and an established biopharmaceutical entity (“Competitor #2”). On a prior occasion, the plaintiff had granted patent rights to Competitor #2, albeit in the context of a settlement and to different patents than the one at issue in this case. These other patents had been exclusively licensed to the plaintiff from an academic entity. Secretariat provided a quantitative evaluation of the terms of the agreement granting rights to Competitor #2 relative to the terms found in the agreement that originally granted the plaintiff rights to these other patents to assess how the plaintiff may approach licensing a potential competitor.

Further, Secretariat utilized financial modeling to assess the relative impact of having the primary competitor in the marketplace to having Competitor #2 in the marketplace in terms of market share in equilibrium. The analysis considered the relative market share impact across a variety of clinical indications in which the companies were expected to compete. Secretariat’s analysis demonstrated that licensing the primary competitor at the hypothetical negotiation was significantly more impactful in terms of equilibrium market share expectations than licensing Competitor #2 had been. See Figure 2.

Figure 2 shows forecasted market shares for the plaintiff across various indications; forecasts are shown assuming both competitors are in the marketplace (gold columns), assuming the primary competitor/the defendant is absent from the marketplace (blue column), and assuming Competitor #2 is absent from the marketplace (red column).

Secretariat’s analysis resulted in two quantitative adjustment factors that were used to account for the competitive dynamics present at the hypothetical negotiation.

Launch Delay: Through its research and discussions with clinical and regulatory experts, Secretariat demonstrated that a potential economic impact from the primary competitor’s launch of the accused product was the possibility for increased regulatory burdens for the plaintiff. In such a case, the plaintiff would likely have experienced delays in entry into the marketplace relative to what would have occurred without entry by its primary competitor. In other words, the primary competitor’s commercial launch of the infringing product could have caused a delay in the commercial launch of the plaintiff’s own product.

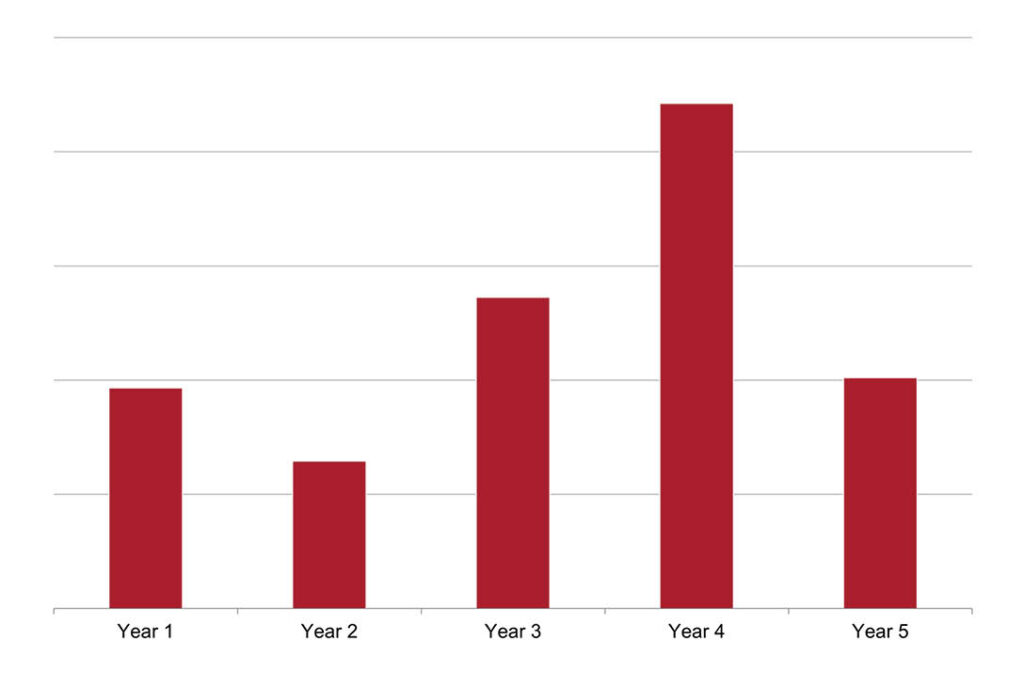

Figure 3 shows forecasted monthly profits by commercialization year assuming no delay in product launch

Using financial modeling, Secretariat forecasted profits from when an unencumbered launch of the plaintiff’s lead product was expected to occur through expiration of the asserted patent. See Figure 3. This forecasted profit stream represents the profits the plaintiff would have expected during a period of patent exclusivity—i.e., had the primary competitor not entered the market until after expiration of the patented claims it had been accused of infringing. Secretariat quantified the financial impact of a commercialization delay of the plaintiff’s lead product through patent expiration by comparing what the profits were forecasted to be through patent expiration without a delay to what profits were forecasted to be through patent expiration with a delay. See Figure 4.

Figure 4 shows the estimated profits lost during each year shown in Figure 3 under a launch delay scenario; Year 5 reflects profits lost through patent expiration

First-mover advantage: Secretariat’s research and analysis included identifying the key considerations for physician adoption and administration of the class of immunotherapies at issue in the matter. Due to the novelty of the therapies, physicians and treatment centers generally lacked experience in their administration at the time of the accused product’s commercial launch. Further, each of the competitors was expected to have specific administration protocols unique to their therapy, thereby potentially limiting the knowledge spillover across various therapies once commercialized. Additionally, the logistics and manufacturing of the therapies was expected to be complicated due to their intensive, patient-specific nature of administration. Thus, adoption of a specific therapy by a treatment center was expected to require a significant investment in time and resources. Secretariat demonstrated through its research that these therapy-specific investments could lead to “stickiness” and “lock-in” within the marketplace, where physicians and treatment centers could be reluctant to offer alternative therapies once available if there is no perceived improvement in safety or efficacy relative to the therapy they have been offering. Secretariat established that the potential for stickiness and facility lock-in presented a first-mover advantage for first entrants into the marketplace that could have long lasting benefits in terms of market share. Using financial modeling, Secretariat quantified the value of the expected first-mover advantage the primary competitor was expected to receive under various market penetration scenarios.

Secretariat offered economic insight and a reliable, transparent evaluation of the likely outcomes from the hypothetical negotiation. The analysis was based on extensive research and a data-driven approach with substantial evidentiary underpinnings. Secretariat demonstrated the robustness of its results to various reasonable assumptions, thereby validating its approach and methodologies. Further, Secretariat’s research and analysis were instrumental in the jury rendering a verdict of damages that precisely matched our trial testimony.

The former NBPA Executive Director, based in Washington, DC, will lead Secretariat’s growing Global Sports Consulting capabilities.

Why Funder Forecasts Don’t Belong in Royalty Analysis

In a recent article published by Law360, Managing Director Rick Eichmann explores the economic reasoning behind the U.S. District Court’s decision in Haptic Inc. v. Apple Inc. and why prelitigation funding forecasts should not be conflated with royalty analyses in patent litigation.

SFO’s ‘Cast-Iron Guarantee’ on Self-Reporting Comes With Fine Print

Ben Boorer, writing for Corporate Compliance Insights, examines the UK Serious Fraud Office’s clearest commitment yet to corporate self-reporting, offering a “cast-iron guarantee” of DPA negotiations for companies that self-report and cooperate.